Carbon Markets

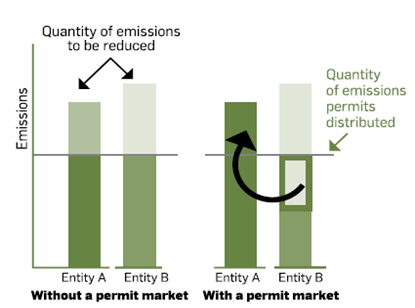

The carbon market is a regulatory-based cost-effective greenhouse gas (GHG or “Carbon”) emission control system where regulators set emission limits for participating countries and enable emission trading in units between countries or sometimes companies by decreasing the overall GHG emission. Aside from curbing down emission levels, the economic cost of reducing emissions can be brought down by enabling trading between entities who can decrease emissions at a lower cost and higher-cost emitters can buy permits from the lower-cost emitter (“Carbon markets-UNDP,” n.d.)

A regulator sets a cap for emission among the participant countries where they need to manage their emissions by the assigned number of permits. Participating countries that can limit their emissions below the set limit can be benefited by selling their permits to countries that want to offset their excess emissions. Regulators have a limited role in this scenario where it only defines the overall cap to fulfill the environmental objective and work as a watchdog to verify the compliance of participating entities. This system ensures economic efficiency without sacrificing environmental efficiency, gives flexibility and cheaper options to limit emissions (Delbosc, 2009). Based on the Kyoto Protocol (KP), credits can be gained by three mechanisms which are Joint Implementation (JI), Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Emission Trading (ET) (Pronove, 2002). But, the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) is the most developed scheme yet (Delbosc, 2009).

Achievements

Two types of carbon markets have been established, one is based on the developed countries under the Kyoto protocol and voluntary carbon market initiated by interested governments, firms, or individuals to reduce their carbon footprint (FAO, 2004). Carbon markets have paved the way for investments in carbon sequestration or any kind of CDM projects in both developed and developing countries (Stephenson and Bosch, 2003). More than 150 bilateral Carbon offset schemes have been developed especially regarding land use projects where 30 projects are related to forestry activities and Carbon sequestration or fossil fuel substitution land use (FAO, 2004). The first intergovernmental trading system including 37 countries that contribute almost 29 percent of global emissions was established based on the Kyoto Protocol and the Marrakesh Accords (Pronove, 2002; Behr et al., 2009). The carbon market was sized at $50 billion in 2007 which is estimated to be a $1 trillion market by 2020 (Melaku, 2015)

Between 2008 and 2016, EU ETS has saved almost 1 billion tons of CO2 emission which is 3.8% less reduction in contrast to a world without the EU ETS (Bayer and Aklin, 2020)

Failures

The carbon market has sometimes been tagged as “Greenwashing” as it can allow polluters to run the business as usual by simply purchasing “carbon credits” to offset their emissions. The price set for carbon credit is also suspected to be very low as the total societal cost of carbon is not considered. There are 64 carbon price schemes launched or planned throughout the world at present which only covers 22% of the total GHG emissions of the world. As more carbon credits were available than demand, the international carbon market collapsed in 2012, though it came back to the limelight again after the Paris agreement (WBG, 2019). The voluntary carbon market is roughly around $300m/year currently which needs to be at least around $50bn-$100bn annually to have a sizable effect (FT, 2020). The international carbon market initiated by the Kyoto Protocol have room for delays and lengthy negotiations which can make room for denials and difficulty in the conviction of any violation (Delbosc, 2009)

Though EU ETS contributed to reducing the GHG emissions, one of the reasons for this reduction could be moving production to other countries with weaker regulation giving rise to ‘Carbon Leakage’ which can be identified as a weakness of the existing carbon market. Such leakages make the impact of EU ETS on global emission weaker than expected (Bayer and Aklin, 2020).

Future Directions

Top-down approaches that are persistent at present will gradually be replaced by bottom-up approaches as countries that are participating in the carbon market will want all other countries to do their fair share (Newell et al., 2013). Existing carbon market policies will necessarily be revised or overhauled under the Paris Agreement framework as impacts of climate change are always uncertain which makes a transparent and orderly revision to carbon market policies mandatory for long-term efficiency (IEG, 2018).

The private sector who is responsible for 86% of global investment (UNFCCC, 2012) is expected to play a vital role in the coming age as companies are supposed to be carbon-constrained both in industrialized and developing countries. By executing Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs), developing countries can also get the benefit of emission reduction. By combining efficient market mechanisms, unilateral and multilateral agreements, a global carbon market can be created ensuring clarity, transparency, and certainty (Ernst and Young, 2013).

The largest developed emitter country USA will have to play a major role to ensure national and global climate change policy by either introducing regulations or programs like emission tax, trading systems (Newell et al., 2013). Developing countries like China, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, and South Africa are expected to be more active considering the detrimental effects of climate change to come up with national climate strategies where the World Bank’s Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR) fund can accelerate a level playing field. As some sectors can be more affected than others by climate change, sectoral mechanisms linking to the domestic emission trading system can stimulate a global carbon market (Ernst and Young, 2013).

With growing carbon markets and emerging market mechanisms, a tendency can come up about linking various markets (Newell et al., 2013) to facilitate at least a partial level playing field, but it will be too far-fetched to expect a truly global carbon market as policymakers can hardly see the big picture going beyond their national interests. To ensure a low-carbon economy, a robust carbon price needs to be implemented so that mitigation measures taken are enough to follow the marginal abatement curve.

Bibliography

Bayer, P., Aklin, M., 2020. The European Union Emissions Trading System reduced CO 2 emissions despite low prices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 8804–8812. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918128117

Behr T. and Jan Martin Witte ,Wade Hoxtell and Jamie Manzer (2009). Towards A Global Carbon Market? Potential And Limits Of Carbon Market Integration. Energy Policy Paper Series, 509. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2060304

Delbosc, A., 2009. Anaïs Delbosc and Christian de Perthuis 40.

Ernst and Young, 2013. The future of global carbon markets: The prospect of an international agreement and its impact on business, URL https://www.eycom.ch/en/Publications/20131022-The-future-of-global-carbon-markets/download (accessed 3 January 2021) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.142

FAO (2004). A Review of Carbon Sequestration Projects. Rome, Italy

Murray, B.C., Newell, R.G., Pizer, W.A., 2009. Balancing Cost and Emissions Certainty: An Allowance Reserve for Cap-and-Trade. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 3, 84-103

Newell, R.G., Pizer, W.A., Raimi, D., 2013. Carbon Markets: Past, Present, and Future 54.

Pronove G. (2002). The Kyoto Protocol and the Emerging Carbon Market.

Scenarios. See https://www.energynetworks.org/creating-tomorrows-networks

Stephenson K. and Bosch D. (2003). Nonpoint Source and Carbon Sequestration Credit Trading: What Can theTwo Learn from Each Other? Paper prepared for presentation at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Montreal Canada, July 27-30, 2003.

UNFCCC, 2012 “Fact sheet — Financing climate change action,” UNFCCC website, http://unfccc.int/press/fact_sheets/items/4982.php, accessed 3 January 2021.